+6

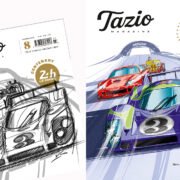

+6 Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

Le Mans 1965, the most unlikely winners

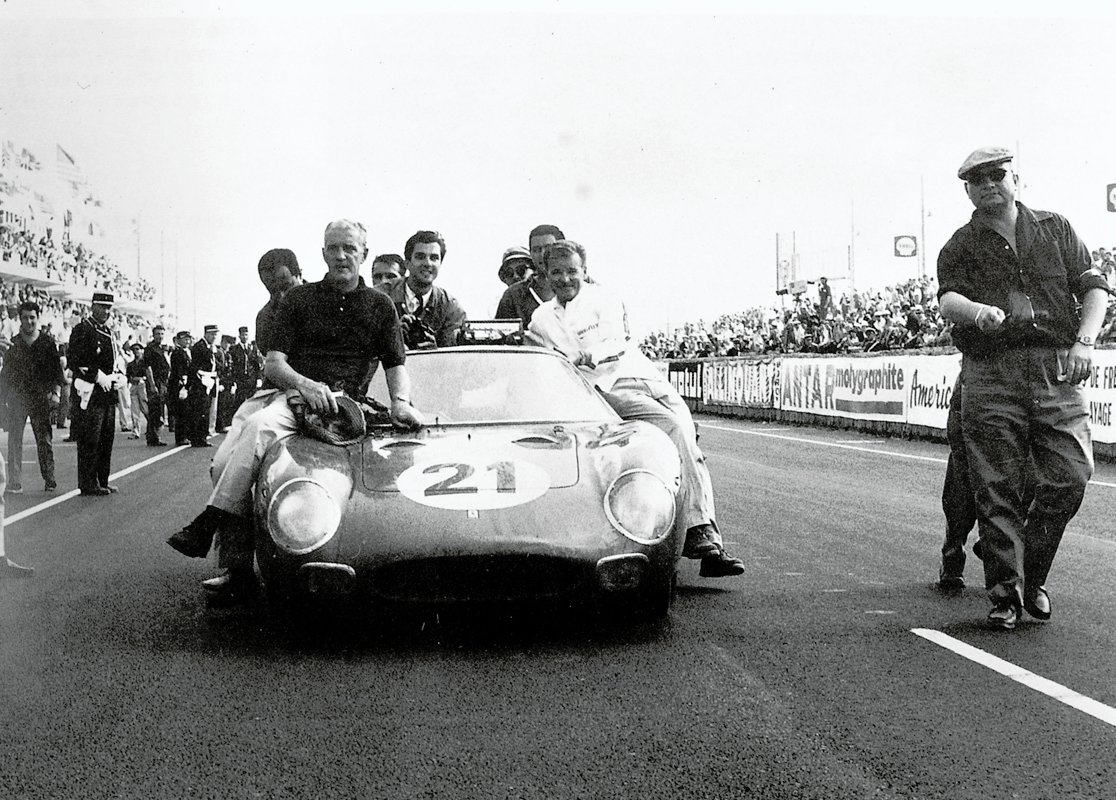

With the Le Mans 24 Hours celebrating its centenary this year, we look back on 24 remarkable races. Today, we bring you the story of 1965, a race bringing many twists and an unlikely duo on the winner’s podium in the end.

Happy Birthday, Le Mans. Thank you for providing the motoring community with a century’s worth of memories. Over the past 100 years, we have witnessed so much of your brilliance, including the creation of motoring legends who are beloved the world over. And no, your madness has also not come unnoticed either. When pondering what year best described this incredibly varied set of qualities, one could not possibly discount 1965. An edition that many would pinpoint as a quintessential Le Mans. A year when a battle between two motoring greats would take its second round, with one of them returning to their stables victorious, though not how originally anticipated.

Indifference

The journey of that year’s Le Mans victor was odd, to say the least. It has become customary for a story’s protagonist to follow a ‘hero’s journey’, filled with obstacles and triumphs. This story’s protagonists: Masten Gregory, Jochen Rindt, and possibly Ed Hugus (don’t worry, we will get to the possible driver in a minute) did not exactly follow this protocol…

Keeping the modus operandi of the late Ayrton Senna in mind, one would assume that any and every racing driver in a ruling class of sports prototypes at the world’s greatest motor race would keep their eyes and ears on high alert, looking for any opportunity to pounce and snatch the lead. Messrs Gregory and Rindt, both at disparate ends in their careers, took a more indifferent approach to competing for one of the motorsport triple crowns.

Ford v Ferrari, pt II

I will not bore you with the details of the war waged on the great racing circuits of the world between Ford and Ferrari. However, this story requires context in the form of the year’s entry list.

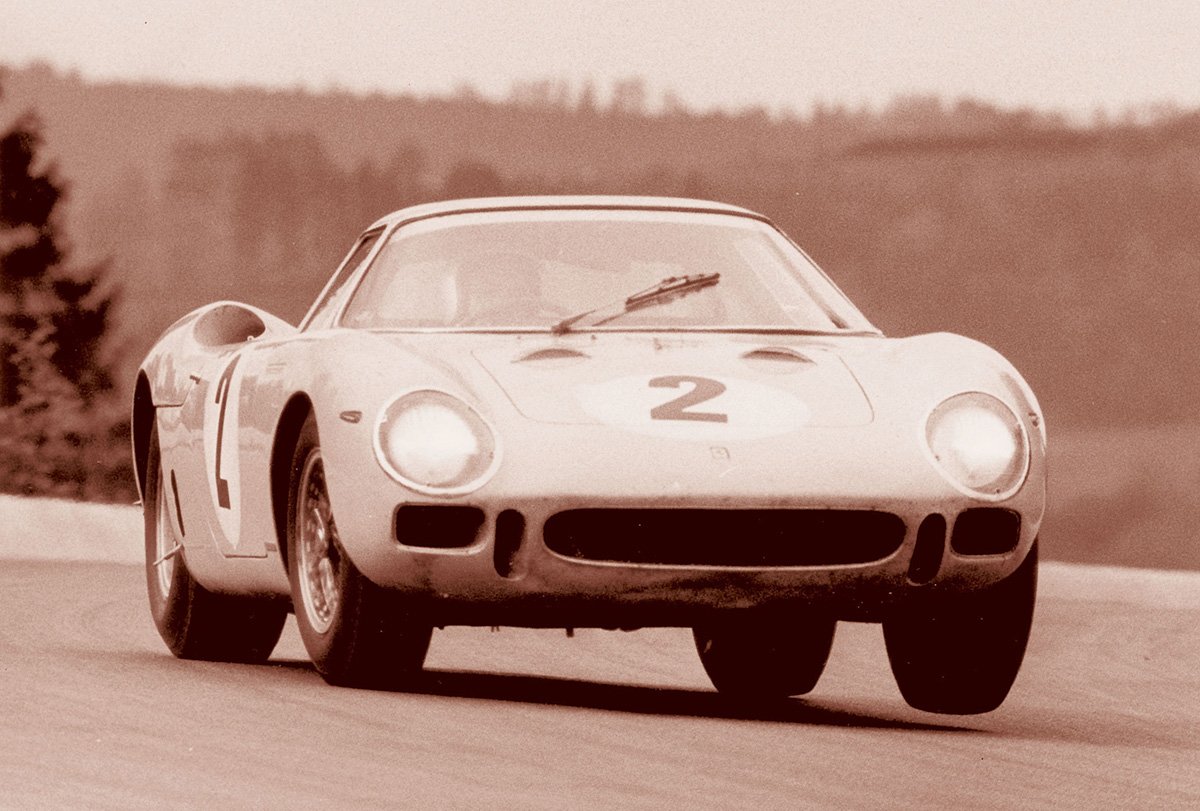

After a dismal showing in 1964, Ford deemed no fewer than six GT40 MKIIs (including two 7.0 litre cars and an additional 4 Shelby Daytona Coupes for the GT category) to be essential equipment in the forceful punting of a posterior belonging to a certain mad Italian hero/tyrant by the name of Enzo. Henry Ford II used less graceful terminology. Ferrari, quite keen to punt in the opposite direction, kept their efforts to a modest ten prototypes (three gleaming 330 P2 lead cars and seven privately entered 250LM domestiques).

In period, those privateer 250LM entries were not viewed as contenders for the Le Mans trophy, unlike the updated Fords and newly debuted 330 P2s. In fact, for all of the 250LM’s win at La Sarthe the previous year, its competition history was in fact a grave mistake.

250 or 275?

Enzo Ferrari originally presented the car to the sport’s governing body as the successor to the front-engined 250 GT lineage for the Grand Touring class. While on paper, there was the similarity of wheelbase length with its Maranello stablemates, there was also the slight snag in that the 250LM obviously had its engine positioned slightly too far rearwards to be a convincing evolution to this front-engined production-based dynasty. Perhaps, that also had something to do with the fact that the LM was essentially the existing 250P prototype with a roof included. In an additional bid to position the LM as a successor to the 250 GT lineage, Ferrari kept the 250 moniker. This was in fact untrue as only the validation prototype used an engine with a capacity of 250 cc per cylinder. All of the customer cars carried a 2755 cc per cylinder motor, meaning that it should have been marketed as a 275 LM. GT homologation, it can be said, was swiftly rejected, forcing the LM to compete as a prototype.

Ford goes KO

Fast forward again to Le Mans in 1965 and the battle is soon underway between the qualifying-crushing GT40s and the proven Ferraris. This is however Le Mans, so the usual array of havoc and problems made their way to the Ford garages, this year in the form of a mighty thirst for fuel in the case of the big 7-litre blocks and a general appetite for gearboxes as well. For Maranello then, the Ford threat was over and done with after only six hours. Perhaps, this would be a good spot to wrap up the story and allow the P2s to coast to a triumphant win and multi-position lockout for the prancing horses. However, with sincerest apologies to Ferrari’s management of the period, Le Mans is Le Mans, so the story continues.

Ferrari woes

Once the evil gremlins of the race had dealt with the Ford effort, they progressed to the Ferrari works pit boxes. In this instance, problems afflicting the P2’s disc brakes and latterly drivetrain failures (probably related to the excessive engine braking after the previous stopping issues) were to throw a spanner in the grand Ferrari masterplan (and this was before the contributions of Signore Binotto and Monsieur Vasseur). Imagine the vexation that arose from the works Ferrari team as the privateers competing with irrelevant LMs filled the first two slots of the running order.

No luck for Ecurie Francorchamps

In the lead by that point was the Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps-entered car with Pierre Dumay and Gustave Gosselin responsible for driving duties. Around midday on Sunday, the woes of Le Mans had struck the bright yellow 250 LM berlinetta down the Mulsanne straight in the form of a 190-mile-an-hour puncture that made itself noticed by tearing through the entire rear-left side bodywork, thus requiring a series of stops before the car could set a consistent pace. This complication was the undoing of an otherwise responsible and consistent run by the Belgian crew that could have resulted in the first overall victory for Ecurie Francorchamps. The same sensibility however, cannot be applied to the eventually triumphant duo.

Break the car

The NART entered 250 LM, piloted by ‘Kansas City Flash’ Masten Gregory and the Austrian Jochen Rindt, had developed a misfire early in the event that led to a pit stop lasting half an hour. At this point, the duo, at the insistence of Rindt, decided to take a rather different approach to completing a 24-hour race. With the realisation that they could no longer compete for a good result, Gregory and Rindt abandoned the conservative approach of driving sensibly in favour of driving the LM to its very limits in the hope of having some sort of mechanical mishap, permitting them to leave early. It is rather incredible that this strategy resulted in their Ferrari completing the rest of the 24 hours without any lengthy, unforeseen pit stops, let alone with the victors’ trophy at the end.

So, have we now reached the culmination of this twenty-four hour long circus? No, we still have some twists and turns to cover.

Dunlop or Goodyear?

As stated previously, the disastrous puncture for the Ecurie Francorchamps 250LM on the Mulsanne straight was most likely the cause for the NART win. However, some internal meddling, seemingly by Il Commendatore himself, could have returned the lead to the Belgian concern. This was due to the fact that it was preferable for Ferrari to have the Belgian-entered car wearing Dunlop tyres win the race as part of a commercial deal with the British tyre company rather than the American-entered car wearing Goodyear rubber. On behalf of Ferrari, a PR man for Dunlop had told Chinetti to slow his drivers down and let the Belgian LM past to victory. Chinetti, however, was not particularly bothered by this order from Maranello and responded in kind to Ferrari through the Dunlop representative. The victory was Goodyear’s first on the international stage.

Ed Hugus

And there is still the loose end that is the enigma of the third NART driver, Ed Hugus. It was long believed that only Rindt and Gregory had covered all 348 laps of the NART 250 LM during the race. That was until a series of letters and interviews nearing the end of Ed Hugus’ life. It was then claimed that Hugus’ had stepped in for Gregory before daylight had struck due to Masten’s vision troubles. However, according to NART team owner Chinetti’s son ‘Coco’, who was present during that year’s edition of Le Mans, “He always claimed to have been the third driver in the LM but I recall quite clearly seeing him from the start to the end sporting a windbreaker and a golf hat!” In addition, famed motorsport historian Doug Nye recently wrote an in-depth analysis proving the unlikelihood of Hugus’ participation in driving duties.

Quite the tale, is it not? In years prior, sorted cars and good fortune had assisted Ferrari in vanquishing their rivals at La Sarthe. 1965 served as an unusual contrast to this usual domination. This was arguably the ultimate Le Mans, featuring pacesetters plagued with mechanical troubles, drivers not particularly motivated to win, political infighting and a controversy that spanned significantly longer than the 24 hours allotted for motor racing between the nineteenth and twentieth of June, 1965.