+6

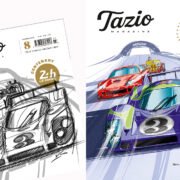

+6 Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

Le Mans 1999, how an experiment led to victory

With the Le Mans 24 Hours celebrating its centenary this year, we look back on 24 remarkable races. Today, we bring you the story of 1999, when an experiment between BMW and Williams led to victory in Le Mans.

It can be said that BMW’s sportscar programme in the late nineties was entirely an experiment. One that served no purpose other than to see whether a positive, productive relationship with the Williams Grand Prix team could be developed before the start of their F1 collaboration at the beginning of the new millennium. However, this programme that created the triumphant V12 LMR was quite a positive prelude to the failed Formula 1 marriage.

Heavy competition

BMW’s winning year in 1999 was another typical Le Mans story. Going into that year’s edition, Mercedes were favoured to win before their CLRs, quite literally, flew far and beyond the competition and into the nearby woods. Out of the remaining probable victors, Toyota was not only eagerly anticipating its first Le Mans crown but also that of a purely Japanese driving crew. At this point, Audi had also launched their vigorously-funded campaign for glory at La Sarthe that would result in the Ingolstadt firm having thirteen Le Mans trophies over the coming decade and a half.

Schnitzer takes over

BMW had also made extensive preparations for that year’s race. Charly Lamm’s Schnitzer concern was selected to run the redeveloped prototype instead of the Italian Rafanelli squadron that had been chosen the previous year. On the matter of the car, 1998’s V12 LM – designed and developed by Williams – required significant redevelopment as that year had been rather bothersome to say the least. The two cars entered were both withdrawn early in the race after wheel bearing issues surfaced. The troublesome car caused a mildly strained relationship, as Williams project head John Russell complained of excessive interference from BMW. It was clear that to secure any hope of success at Le Mans, an effort of enormous proportion was required…

Small roll hoop

On the matter of aerodynamics, distinguished designer Peter Stevens and Graham Humphreys of Williams were recruited to revalidate the aerodynamics of the car. As a byproduct of the aerodynamic developments, the V12 LMR was significantly more pleasing in terms of aesthetics, carrying a puristic energy about it that translated to a shape that seemed entirely natural in a racing environment. More importantly, however, this new styling brought a significant aerodynamic advantage due to an ingenious, typically F1 interpretation of the regulations that allowed an elegantly-integrated hoop rather than a complex full roll bar commonly used in period. Additional modification to the McLaren F1 GTR-derived engine was performed, resulting in a motor that weighed twenty kilos less.

This carefully considered engineering programme was proven when the new V12 LMR returned to Munich victorious and battle-tested from twelve hours of racing on Sebring’s notoriously punishing pavement in 1999.

“We come to win”

Fast forward to Le Mans later that year, the BMW teams’ spirits could be described as lifted but sensible, after all they faced stiff competition from Mercedes, Toyota, and Audi. However, when asked of BMW’s intentions at La Sarthe, BMW’s newly appointed joint head of Motorsport, Mario Theissen, unambiguously responded; “Of course we are here to win.” This proclamation was to the unsettlement of Schnitzer boss Charly Lamm and joint head Gerhard Berger. So, no pressure then…

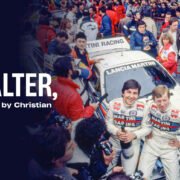

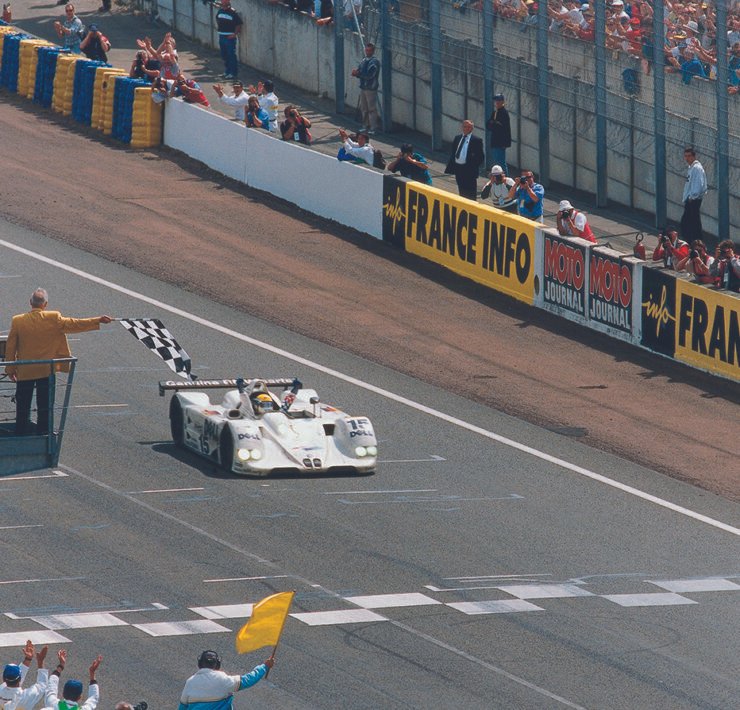

The 1999 edition of Le Mans is marked by Mercedes’ aforementioned flying incidents that ultimately led the silver arrows to withdraw their cars from the race and cancel their CLR programme, turning control of the event entirely to Toyota and BMW. Toyota had lost two of their three GT-One cars as a result of separate incidents during the nighttime. Thus, a one-two finish was in sight for the LMRs, that was until the throttle on JJ Lehto’s car stuck wide open, which led to a collision with a barrier at approximately midday, injuring the Finn and leaving just one BMW in the race.

High speed puncture

A final duel commenced between the sole remaining GT-One of Toyota and the V12 LMR of BMW, prompting Toyota driver Ukyo Katayama to break the lap record at La Sarthe in a last attempt to catch Pierluigi Martini in the BMW. However, in the final hour and with only a few seconds separating the two cars, a tyre on Katayama’s Toyota punctured at high speed after a collision, allowing Martini to cruise to the finish, securing BMW’s first Le Mans win. One would assume that this great victory would foretell a BMW Williams success story in Grand Prix racing, although this is a story to be told on other circuits.

You can read more on this subject in issue 5, where we talked at length with both Mario Theissen and Pierluigi Martini on the BMW V12 LMR. Available here.