+1

+1 How Chinetti and Levegh preferred flying solo

How Chinetti and Levegh preferred flying solo

How Chinetti and Levegh preferred flying solo

How Chinetti and Levegh preferred flying solo

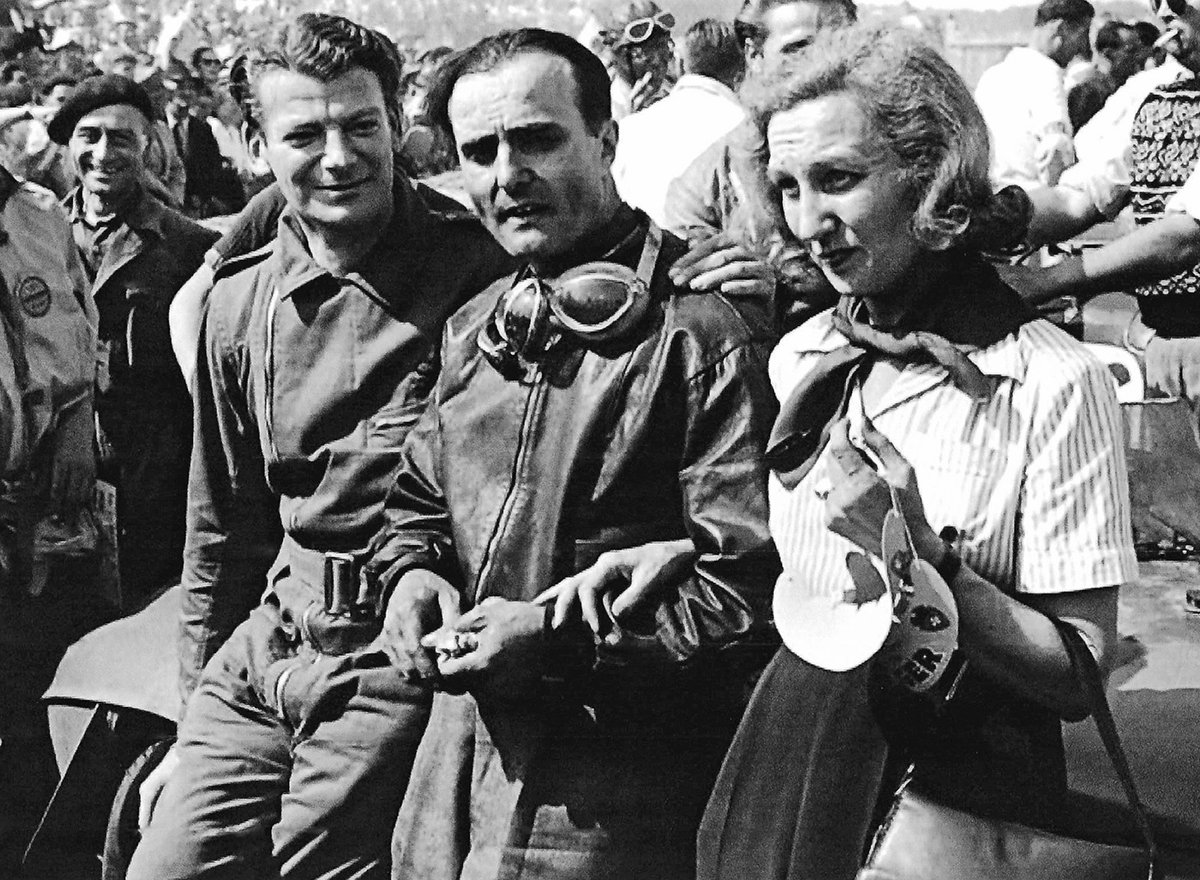

In this episode on the Le Mans 24 Hours’ centenary, we look at two almost-solo exploits. Luigi Chinetti’s successful run to victory in 1949 and Pierre Levegh’s nearly-successful attempt in 1952.

Le Mans, as I am sure you are all quite aware, is not the average motor race. It is arguably the greatest test of man and machine. It is daunting enough to undertake such a great task in the space of a stint, or even a double or quadruple stint repeated at points throughout a race, let alone the great distances travelled by messrs Levegh and Chinetti on their respective drives in search of triumph at La Sarthe.

Newcomer Ferrari

We start our tale with the 1949 edition, when Luigi Chinetti would achieve his third Le Mans trophy, and perhaps more importantly, Ferrari’s first of ten. This edition was also the first held since the conclusion of the Second World War and yielded 52 entries, a healthy increase over the previous event in 1939. The revival of the classic endurance event was postponed due to lengthy renovation as a result of extensive damage to the circuit during the war.

Contenders for the 17th Grand Prix of Endurance included the French marques of Delahaye and Delage that were entered to the large-displacement classes. In addition, the newcomer Ferrari made its first appearance as a constructor with two entries, though not as a works effort. Il Commendatore was not sure of the 166 MM’s durability at the endurance classic, despite its great success with a 1-2 victory earlier that year at the Mille Miglia.

Dreyfus crashes

When the race was underway, the Delahaye of Eugene Chaboud burst ahead. This established control of the lead by the French manufacturer for the inaugural four hours until nine in the evening, when the Ferrari of Pierre-Louis Dreyfus snatched first position from them. This was a result of Flahaut’s Delahaye 175S losing considerable time due to engine troubles as well as Pozzi’s leading car suddenly catching fire on the Mulsanne straight. Dreyfus would later overturn his Ferrari at the White House corner in the increasing darkness, thankfully surviving the accident. The Talbot of Guy Mairesse and Paul Vallee would inherit first position, though followed closely by the second 166 MM. Control of the race would soon fall to the Ferrari of Luigi Chinetti, who had driven the entire event up to that point.

At around five in the morning and after establishing a three-lap gap, Chinetti would hand over driving duties to the car’s owner, Lord Selsdon. Despite some experience in motor racing, Mitchell-Thomson (the aristocrat’s given name) was not able to increase the lead and was losing time to a Delage at approximately six and a half seconds per lap. In fact, the Briton would complete only 72 minutes of the twenty-four hours, supposedly due to falling ill. There are many theories as to why such a short distance was accomplished by Lord Selsdon. One of them suspects that he gave himself a fright during his stint and did not desire any additional driving.

22 hours and 48 minutes of driving

Before the arrival of the seventh hour of the new day, only 27 of the original 52 cars remained in competition at the Circuit de la Sarthe. It was around that time that the Delage of Louveau took a series of stops as a result of grave trouble with its thre- litre, straight six engine, losing half an hour in the process and handing an advantage to the Ferrari. Chinetti, though, had a setback of his own when repairs had to be performed to the front of his chassis. The lead, however, remained his.

Tragedy struck at around one in the afternoon when the fourth-placed Aston Martin DB2 of Pierre Marechal had overturned at White House, leaving the driver with severe injuries that would result in his death the following day. The race finally concluded three hours later with the tireless Chinetti completing an epic tale in the Le Mans records by winning the Grand Prix of Endurance by driving an incredible 22 hours and 48 minutes.

Almost

One could also claim an equally impressive feat by Pierre Levegh about three years after Chinetti’s triumph. Except, the Frenchman narrowly missed out on his Le Mans trophy…

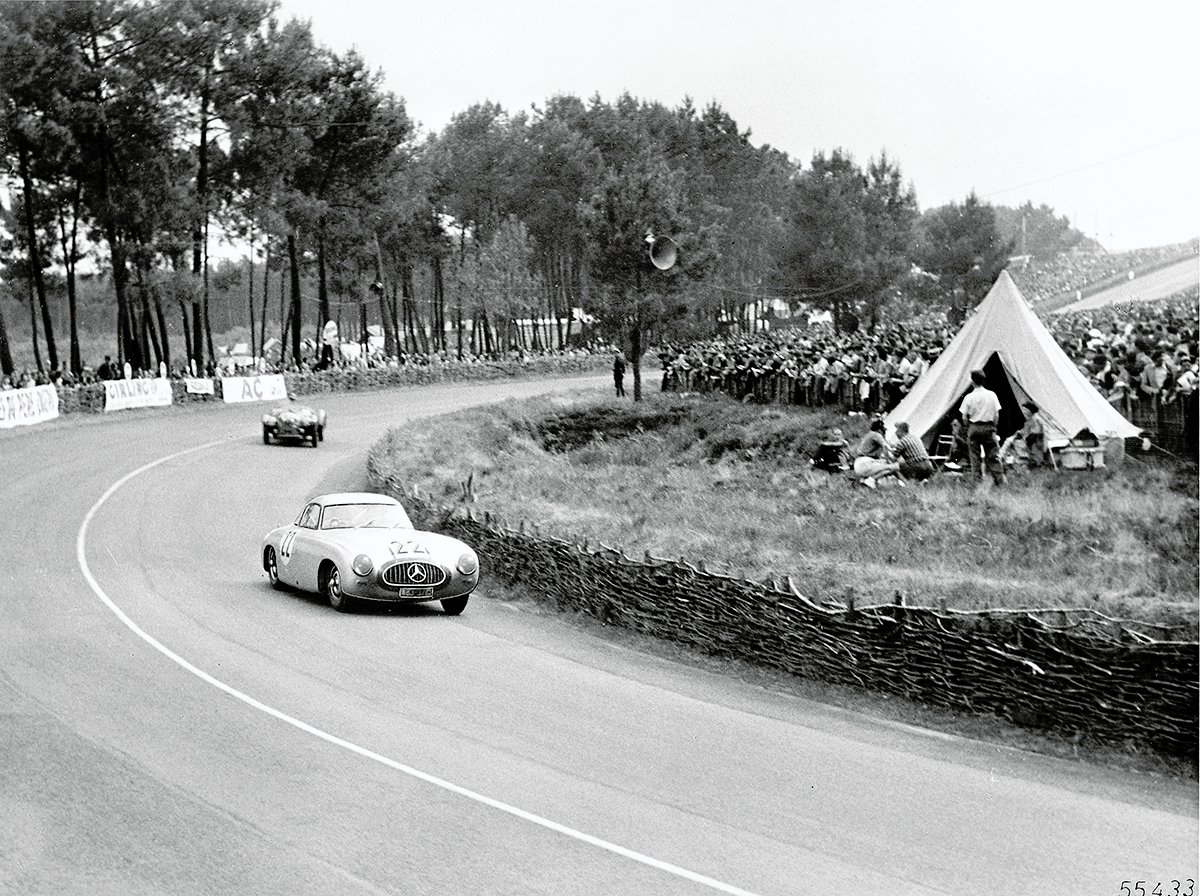

The 1952 edition was highlighted by the works entries of several marques. Aston Martin had finally decided to showcase its new DB3, though it was expected to be underpowered and overweight. Ferrari had also returned with no less than seven cars and four of those being 4.1-litre 340 Americas. Additionally, the American challenge came from pioneer Briggs Cunningham with his V8-propelled C-4R racers. Mercedes had also entered their new 300 SL Gullwings with great prior success at other sportscar events such as the Mille Miglia.

“Must have more speed”

Jaguar was one of the expected victors, having returned to their Coventry headquarters victorious the year prior with their legendary C-Type (officially entered as an XK120C). The British manufacturer had returned to La Sarthe sporting C-Types with modifications that promised even greater aerodynamic efficiency. These changes were performed after Stirling Moss sent a telegram directly to Sir William Lyons simply stating “must have more speed at Le Mans”. This message was in response to Moss being overtaken at great velocity by one of the new Mercedes W194 Gullwings.

Thus, famed aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayers carried out changes to the nose of the Jag that reduced the air intake in size and repositioned the radiator. During the cat’s week at Le Mans, the team would desperately try to fix an overheating problem on the newly-dubbed ‘Kettle Cars’ with hammers. This was to no avail as all three C-Types were to retire as a result of these rushed alterations. If only they knew that Mercedes had practised the Italian road race weeks before the commencement of the Mille Miglia…

The French efforts of the likes of Gordini and a privately run Talbot-Lago did not have great expectations against the works squadrons mentioned above. This was why it was to everyone’s astonishment when the Talbot-Lago T26 GS Spyder of Pierre Levegh stormed into the lead after the factory entries of brands as Ferrari, Jaguar, Cunningham and Aston Martin had exited the leaderboard. The Gordini T15S of Jean Behra and Robert Manzon was also being piloted vigorously.

Bentley tactics

By contrast, Mercedes team chief Alfred Neubauer followed the Bentley tactic at the turn of the 1930s, when their cars drove at minimum pace in a bid to last the gruelling event. The race proceeded with the 47-year-old Levegh driving the entire distance, thus far without any driver changes and whilst maintaining first position. The Gordini of Manzon, however, did not escape the gremlins of La Sarthe despite what Motorsport described as “terrifying speed”. The car visited the pits at about half past three in the morning with brake troubles. It seemed that the front brakes had enough. Drivers Manzon and Behra attempted to persuade Amédée Gordini to permit them to continue with only the rear brakes, yet Gordini was unconvinced and withdrew the car.

By 9 AM and 17 hours into the race, the Talbot-Lago of Levegh maintained a four lap (or twenty minute) distance ahead of the Mercedes’. The German team evidently began to display their concern through their increased pace. Nevertheless, they could not catch the lone Frenchman. Motorsport also recorded that “Mercedes-Benz was obviously content with second and third places.” In spite of his ageing roadster, Levegh (or Pierre Bouillin, by birth) was capable of setting lap times at a greater speed than the victorious C-Type from the year prior.

Retirement

After almost 23 hours, Levegh’s campaign to win Le Mans solo would come to a crushing end. It was 23 hours of tremendous difficulty that included sickness in the car, and arguments with his capable teammate René Marchand (and wife) in order to stay out on the circuit. The challenge would break down (if you will excuse the pun) due to the engine in the Talbot-Lago halting. Just as our previous Le Mans tale of long drives, there are several theories as to the causation of the retirement.

Some say that Levegh had succumbed to exhaustion and missed a gear shift. Others argue over whether the crankshaft or big end had given in. Conversely, additional evidence claims that Levegh was aware of engine vibrations at the start of the race, leading him to believe that only he had the mechanical sympathy required to last the distance, not his skilled teammate Marchand. This was not adequate to halt the inevitable as the Mercedes Gullwings would roar past Levegh’s lead and onto a one-two victory for Mercedes. In the process, cementing a competition legacy for the future road-dwelling Gullwing to rely upon.

Le Mans, 1955

Despite Levegh’s run falling short of a victory, this achievement was given a special place in Le Mans history and established his determination as a driver. That determination would catch the eye of a certain Alfred Neubauer, who would in 1955 award the Frenchman a drive at the works Mercedes concern. Levegh and the Mercedes 300 SLR would write history once more at Le Mans in 1955, unfortunately for all the wrong reasons.

These great heroics from the likes of Chinetti and Levegh cemented respective legends. Indeed, their rather lengthy stints truly represented Le Mans’ mission to test the endurance of man and machine against the elements. Whilst the test of mechanical endurance continues, the test of a human’s endurance will never be replicated to the same extent as the ACO would mandate driver time limits from 1953 onwards.