+6

+6 Le Mans 1999, Mercedes Aviation Academy takes off

Le Mans 1999, Mercedes Aviation Academy takes off

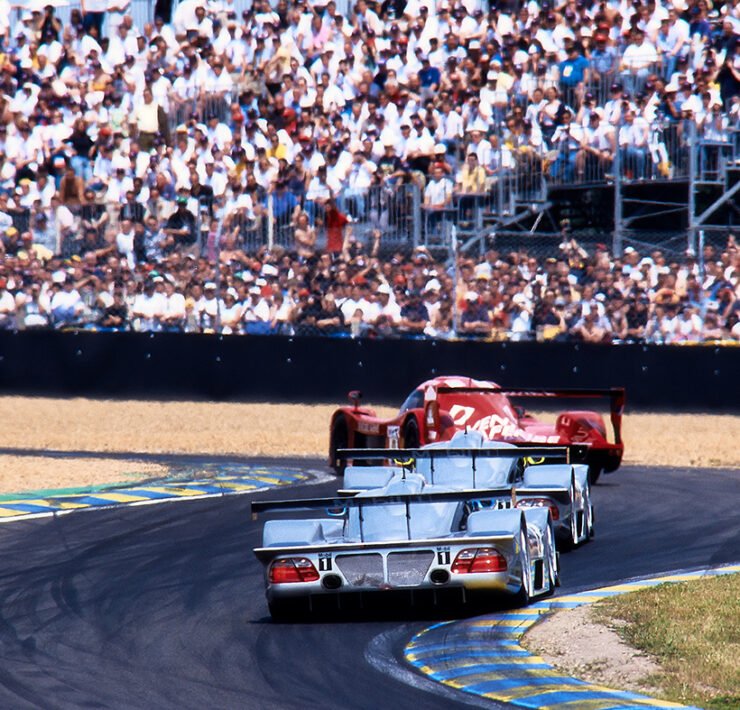

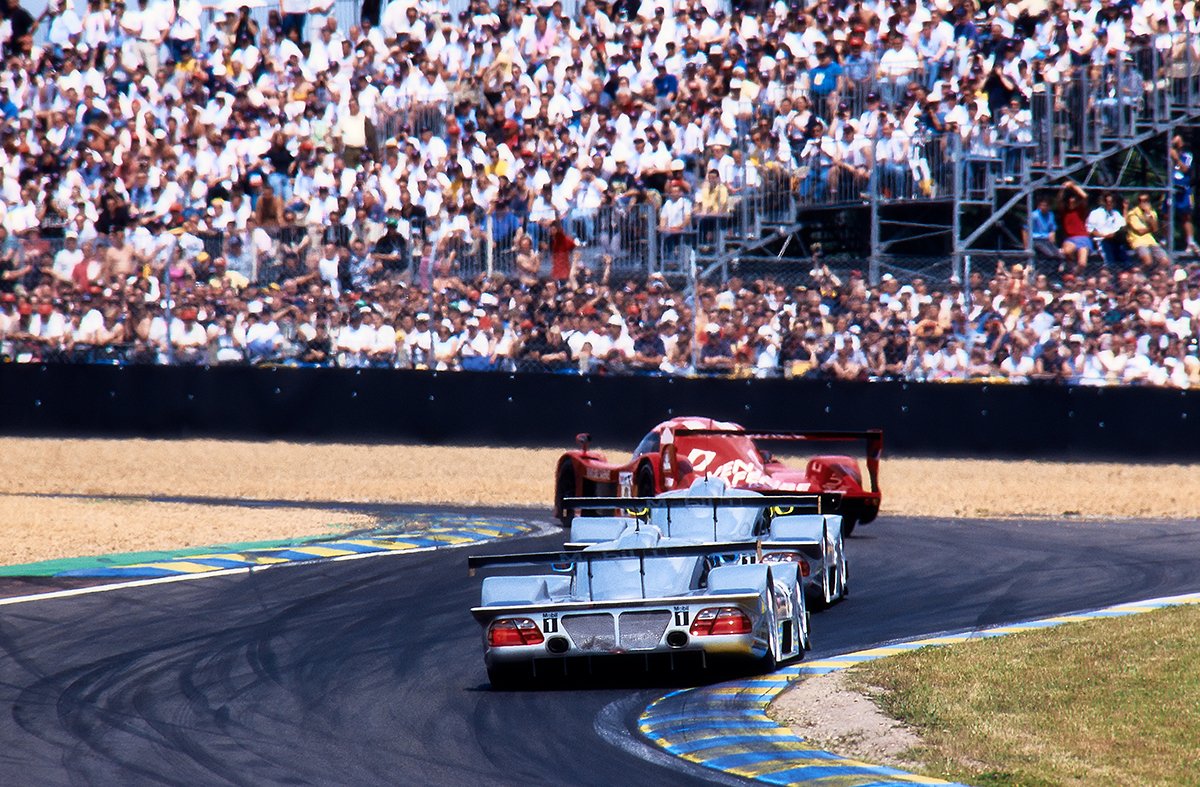

1999 was – so far – the last year we would see Mercedes at Le Mans. It become the year that was known for the Mercedes flying circus acts with the CLRs, a page the company would rather forget.

So far in this series of articles on the centenary of the Le Mans 24, we have covered everything from political infighting, unmotivated drivers, wins that served a larger purpose, and much more (please do view our previous articles on our ‘100 Years Le Mans 24H‘ page). However, not a single flying car has graced these virtual pages, so perhaps it is time to rectify this.

GT1 becomes LM GTP

BMW’s glorious victory in 1999, detailed in our previous article, was both experimental and mostly unforeseen. As previously mentioned, this was due to a lack of a competitive record (aside from a victory at the Sebring 12 Hours earlier that year) as well as formidable opponents, especially in the form of certain prototypes-in-the-form-of-GT-cars in the traditional shade of ‘German Racing Silver’ and an embedded three-pointed star.

Mercedes had proven itself in its quest for sportscar dominance in the late nineties by carefully studying its rivals and fully exploiting the given regulations to the point of winning the FIA GT1 Championship in 1997 and winning every race in the 1998 edition of said championship with the CLK. Seeing these specifically created GTs in name only – regulations required just the one existing road car as a basis for homologation – GT1 was buried and replaced with the ‘LM GTP’ class especially for Le Mans.

Slick CLR

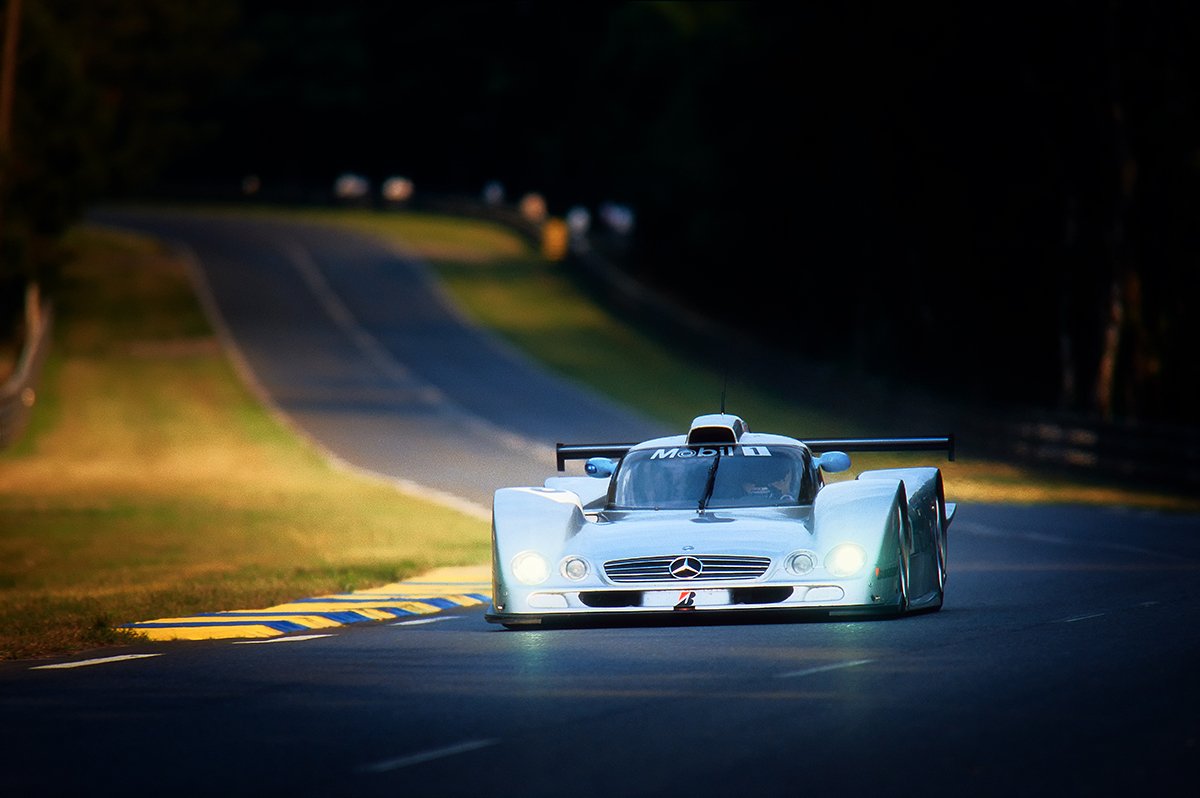

The Silver Arrows took full advantage of these new circumstances as before, responding with the CLR, a new development in this recent lineage of sports prototypes disguised as GT cars. With heavy emphasis now on dominance at La Sarthe, aerodynamic redevelopment was of utmost importance.

Le Mans is of course a circuit occupied by rather lengthy straights, most notably the Mulsanne (since 1990 broken in three sections, interrupted by two chicanes). Thus, a car with low drag to maximise terminal velocity on these predominant straightaways is undoubtedly a key to success. However, one must also take into account the requirement of reasonable downforce to keep adequate pace on Le Mans’ numerous high-speed corners.

Pitch-sensitive

Mercedes, it could be said, bolded and highlighted the former part of this aerodynamic to-do list far more than the latter. For example, the CLR’s wheelbase was shortened to maximise overhang. Thus, allowing Mercedes to carefully curate the aerodynamic properties of the car, especially in the matter of underbody development that permits more drag-efficient downforce. Most critically, perhaps, was Mercedes’ focus on neutralising the CLR’s pitch angle. Utilising a car’s pitch angle is a fundamental aerodynamic tactic applied to increase downforce by having a lower front end in contrast to the rear, at the expense of drag.

The Silver Arrows’ solution was to neutralise this by having a pitch angle of approximately -0.7 degrees as opposed to some of its LM GTP peers with approximately -2.5 degrees. This was too extreme a measure in Mercedes’ pursuit of ‘the unfair advantage’, as was proven by the pitch-sensitive cars’ three take-offs that occurred at the various runways of what became the Le Mans International Airport.

Webber’s first flight

The first flight took place when approaching Indianapolis corner during qualifying on Thursday in the hands of a certain future F1 star that has proclaimed himself as “not bad for a number 2 driver.” Following in the slipstream of another prototype on a bumpy stretch of tarmac in between the Mulsanne and Indianapolis corners, both factors negatively affected the front end’s ability to produce downforce, thus causing a disturbance in pitch and astonishingly generating such significant lift that Mark Webber’s CLR became the first successful launch for Mercedes Airlines. Miraculously, Webber completed a full loop and landed on all four wheels, whereupon the CLR hit the barriers. He escaped unharmed and reported the incident to his team.

Quick changes

Webber was at first dismissed due to the absence of photographic, televised, or other first-hand witness evidence. According to Webber’s autobiography, the Mercedes crew simply responded ‘No that couldn’t happen, the car couldn’t possibly flip end over end.’ Mercedes had consulted with then Technical Director of the McLaren-Mercedes Grand Prix team, Adrian Newey. It is said that Newey advised Mercedes to withdraw from the event. Instead, Mercedes altered the car by adding dive-planes at the front normally reserved for the wet as well as stiffening the rear suspension.

Webber flies again

On Saturday morning, Mark Webber was once again driving the CLR, on this occasion during the pre-race warm up. When following another car over the hill approaching Mulsanne corner (is there a pattern developing at this point?), Webber’s rebuilt CLR again manifested its aviatic ambitions despite the aero modifications. Again, Webber walked away from the incident, only this time the cameras had captured the incident and broadcast the flying Mercedes live around the world. and would not start the 67th edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Mercedes, however, continued to deny the evidence of the CLR’s fundamental flaw. The #4 CLR of Webber – Tiemann – Gounon was withdrawn from the race, but both the #5 and #6 CLRs started the race like nothing had happened. The drivers were warned ‘not to follow other cars too closely.’

Dumbreck’s turn

Seventy-five laps into the 1999 Le Mans 24 Hours, a Mercedes once again took flight in what became the most widely publicised takeoff of the three. On approach to the Indianapolis corner, Peter Dumbreck’s #5 CLR followed in the slipstream of a Toyota GT-One. The Mercedes took off once more for good measure, and additionally opted to send itself and its driver over the barrier and into the nearby forest.

It was an incredible stroke of luck that the car landed in a 100-metre wide patch of area where all of the trees had been recently chopped down. Dumbreck would also walk away from what could have been an accident that might have claimed his life, like it had happened to Jo Bonnier before. Mercedes withdrew the #6 car at once, flying lessons were over.

ACO makes changes

In response to the accidents, the ACO shortened the maximum overhang length on prototypes, smoothed out the bumpy sections of the public road that comprise a considerable amount of the Circuit de la Sarthe and flattened the infamous crest at the end of the Mulsanne straight.

Mercedes’ PR slogan of course follows the words of Gottlieb Daimler, ‘Das Beste oder nichts’, translated to English as ‘The Best or Nothing’. Mercedes, immediately cancelled its racing programme for 1999 and seeing that it could not win Le Mans without an even greater location of resources towards a prototype programme for the following year, selected the ‘or nothing’ option and has not returned to La Sarthe in any capacity since.

Our columnist Christian Geistdörfer was in the Mercedes hospitality that weekend at Le Mans. In issue 8, he remembers that shocking weekend.