+31

+31 Le Mans 1991, when Mazda plays the smartest game

This week’s telling of a Le Mans tale travels in time approximately 22 years after last week’s story of Jacky Ickx’s and Jackie Oliver’s remarkable victory in the Ford GT40. This week uncovers yet another incredible victor, arguably the most unlikely in Le Mans history: the remarkable Mazda 787B at the 1991 edition of the Le Mans 24 Hours.

The 1991 edition was a transitional year for sports prototypes, moving from the existing Group C cars to the new 3.5-litre, Formula 1-inspired engines. These new prototypes were championed by works efforts that were not financially constrained, such as TWR Jaguar, Sauber Mercedes, and Peugeot.

As a result, these new regulations proved unpopular with privateers, leading to the shortest entry list for the French endurance classic in approximately sixty years. In addition, the new 3.5-litre prototypes were designed for the seven other rounds of the World Sportscar Championship. Races that only covered 430 kilometres of distance, rather disparate to the previous 1000-kilometre races, let alone the approximately 4,900 kilometres driven by the eventual race winner at Le Mans.

Old Group Cs

The TWR Jaguar and Sauber Mercedes teams had realised that their new prototypes would not be able to last the distance, and opted for an unusual tactic, to say the least. Instead, they would run their new prototypes through the qualifying session (with tremendous pace with simultaneous unreliability), and then swap to the old Group C machinery for the actual event. Oddly, however, Jean-Louis Schlesser’s turbocharged Group C Mercedes managed to qualify 3.7 seconds clear of the quickest three-and-a-half-litre prototype.

Category 1

To add to the oddness, the organisers placed significant penalties greatly affecting the performance of the Group C cars, such as heavy ballasting, lower grade fuel, slower fuelling systems, a more stringent cap on fuel consumption, and due to the unexpected pace from these seemingly irrelevant competitors, a mandate that declared that all Category 2 cars (Group C that were due to be banned the following year) were to start the race behind the Category 1, 3.5-litre prototypes.

However, it should be clarified that not all Group C cars were affected by regulatory setbacks.

Low weight limit for Mazda

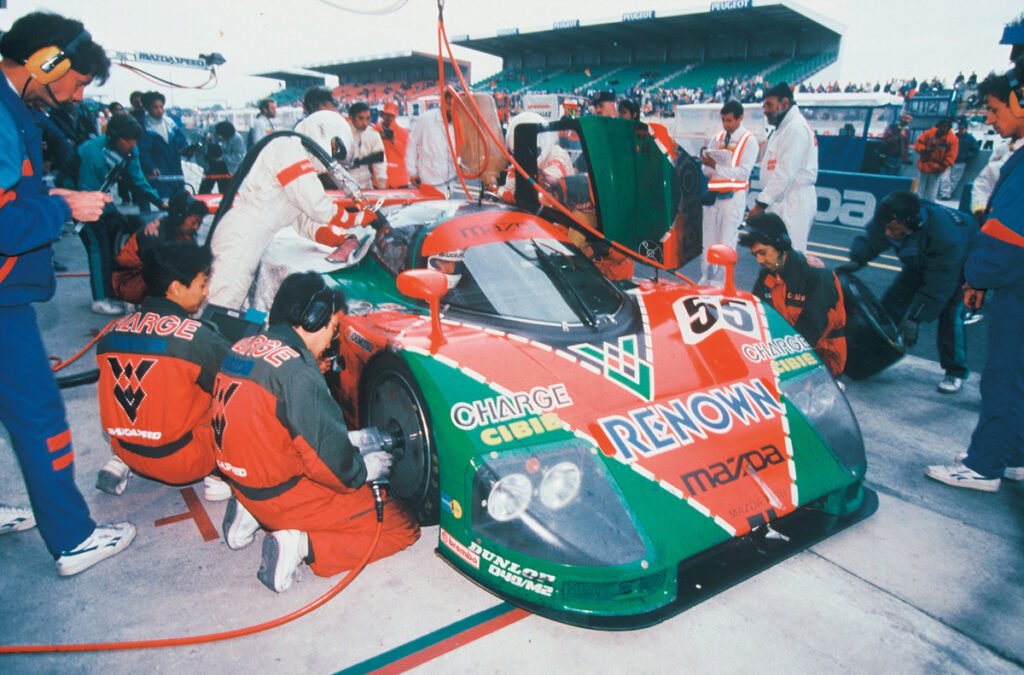

The previously unsuccessful Mazdaspeed squadron had managed to argue that the weight ballasts should not be applied to their newly developed 787B due to their small capacity rotary engine. Thus, they raced at 830 kilogrammes, when most others were ballasted to circa 1000 kilogrammes. The ACO had permitted Mazda to run lower weight in an effort to keep entry numbers afloat, with particular emphasis on those of Japanese participants.

Carbon

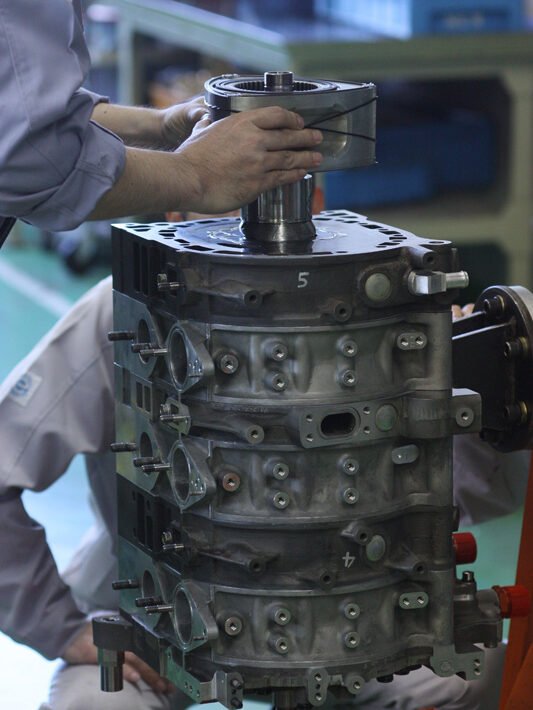

Mazdaspeed had also heavily redeveloped their existing prototype to have more of a chance for a respectable result at their final Le Mans. A significant change was conducted when designer Nigel Stroud and long-term team boss Takayoshi Ohashi convinced the Mazda board to finally invest in a carbon fibre monocoque as well as carbon brakes.

On the motor aspect of development, Mazda utilised a four-rotor engine, producing 700 hp in endurance specification (and purportedly 900 hp in derestricted form). In an interview with Motorsport, Stroud confessed to the difficulty of working with the Wankel engine, “the rotary bit is a non-stressed member of the car. So it’s very difficult to go to get enough rigidity in the engine bay area.”

Additionally, Stroud shared that “The 787B really was just capitalising on everything we’d learned with the 787 and 767 and making everything better – better brakes, better engine etc.” The aero package of the 787B was also developed with La Sarthe’s long straights in mind, especially the Mulsanne that, unfortunately for Mazda, had been split in three for the 1991 edition.

Smooth engine

Mazda’s quintessentially unique perspective to motorsport development with the rotary engine certainly had its pros and cons. On the pros list, fuel economy was superior to their piston-powered rivals. Additional positives included superb drivability, reliability and smoothness (driver Johnny Herbert proclaimed the R26B as the smoothest engine he had ever driven).

On the cons side, however, was lower torque in comparison to their prototype peers, especially those equipped with turbochargers. In fact, said torque deficit was a major factor in Mazda’s lack of success at other, shorter rounds of the World Sportscar Championship.

Ickx consults

Fast forward to the start of the 59th edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the racing world did not have great expectations for the two Mazdaspeed-entered prototypes; despite their permitted lower weight, efficient rotary engines, three F1 drivers, illustrious consultant Jacky Ickx (six-times Le Mans winner who we covered in our previous article on the 1969 edition) and orders to drive flat out for the duration of the 24 hours.

As the race commenced, the Category 1, 3.5-litre Peugeot prototypes roared ahead of their Group C counterparts to the delight of the local crowd as a French team had not won for over a decade. However, it can be said that the Sauber Mercedes and TWR Jaguar teams merely allowed the Peugeots to lead for the period of time before the highly-strung prototypes would inevitably encounter major mechanical troubles. After all, it would be a shame to waste all of that heavily limited fuel supply…

No luck for Mercedes

After the leading Peugeots decided that a 24-hour race was too much to expect from a sports prototype, two of the Sauber Mercedes finally duelled for the lead. They were eventually joined by an additional C11 to establish a Mercedes 1-2-3. During the nighttime, in fact, a young lad named Michael Schumacher – yet to make his mark on the world of motorsport – set the quickest lap of the race.

However, a typically Le Mans twist to the tale had begun to unfold as the race progressed. The third-placed Mercedes C11 car had retired from the event as a result of an engine failure. To add to the blow, the once-leading Silver Arrow driven by Schumi dropped out of contention as a result of gearbox troubles. Fifth would be the best he and fellow-Juniors Karl Wendlinger and Fritz Kreuzpointner could manage.

Pressure

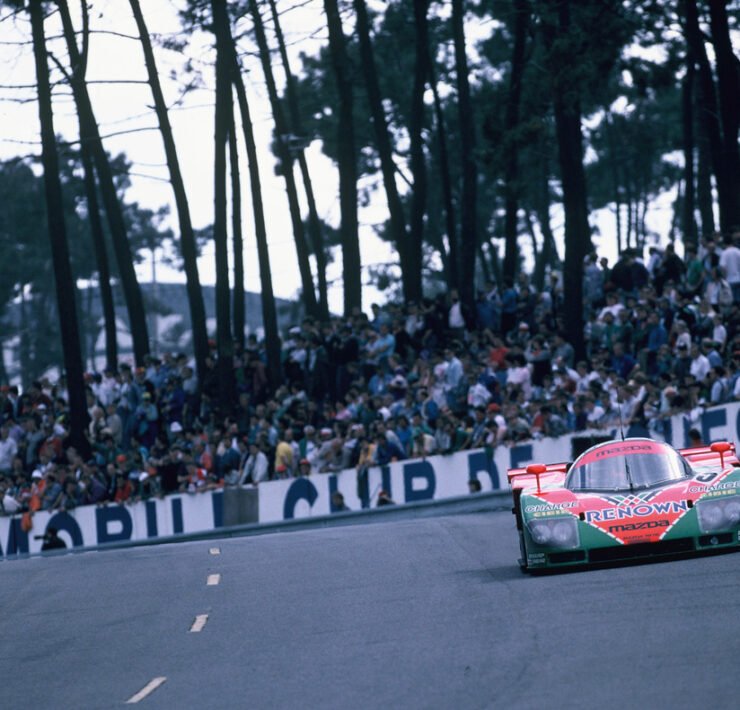

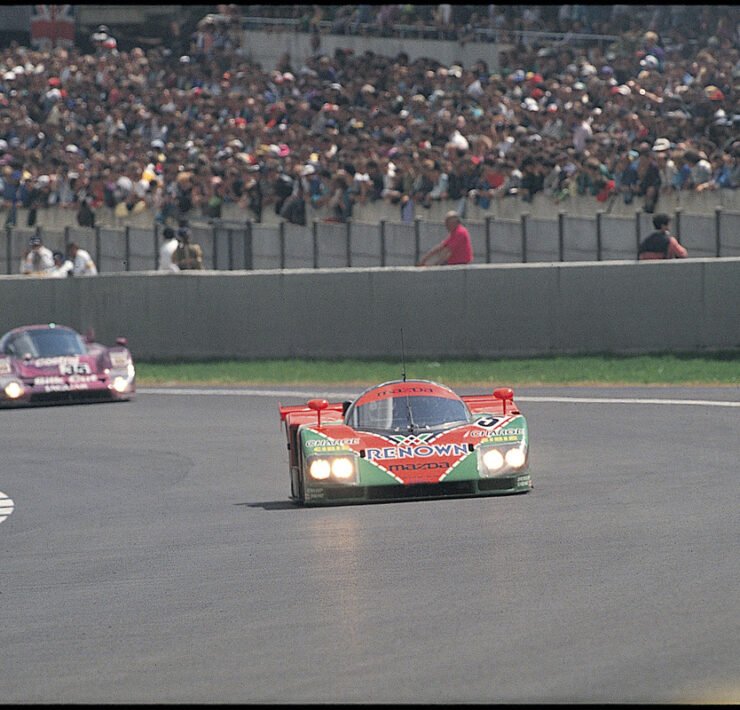

The Mercedes challenge came to a tragic halt before one in the afternoon on Sunday when the #1 Mercedes C11 ran into trouble with gearbox wear and an overheating five-litre, turbocharged V8. At this point, the #55 Mazdaspeed-entered 787B, driven by Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler and Bertrand Gachot, entered the lead after considerable time spent steadily pressuring the C11 into trouble.

The quirky, rotary-powered racer from Hiroshima kept the two works TWR Jaguars at bay for the remaining few hours of the event to finally win the French endurance classic after thirteen attempts by Mazdaspeed. In the process, it became the first Japanese victor at Le Mans and the first car to win without a conventional piston engine. It is said that the R26B, four-rotor engine would have been able to last another 24 hours with just a simple oil change.

Herbert to hospital

While drivers Bertrand Gachot and Volker Weidler celebrated at the podium with the traditional spraying of champagne, the third driver, Johnny Herbert, had to be transported to hospital after driving long stints with severe dehydration. In an interesting parallel between man and machine, the chassis of the winning 787B was stressed to an inch of its life, unlike that iconic rotary whose sonority and outlandishness left the spectators and viewers of the 59th edition of the Le Mans 24 Hours speechless and forever in awe.

Read the other articles on 100 Years Le Mans 24 Hours here.